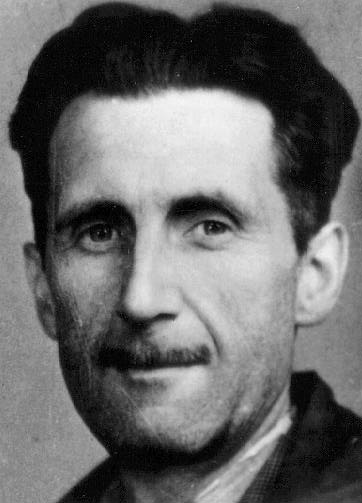

“George Orwell” was born Eric Arthur Blair on June 25, 1903 in Bengal, which was then a British colony in India. He went to Wellington for one term on scholarship, then moved to Eton, also on scholarship. After Eton, he joined the Indian Imperial Police in Burma from 1921-1928. He resigned and moved back to England.

“George Orwell” was born Eric Arthur Blair on June 25, 1903 in Bengal, which was then a British colony in India. He went to Wellington for one term on scholarship, then moved to Eton, also on scholarship. After Eton, he joined the Indian Imperial Police in Burma from 1921-1928. He resigned and moved back to England.

He adopted the pen name George Orwell in 1933 while he was writing for New Adelphi. George came from St. George, the patron saint of England, and Orwell was from the River Orwell in Suffolk, a favorite English site.

He lived in poverty for some time and wrote about it in his first novel, Down and Out in Paris and London (1933). His next novel, Burmese Days, was published in 1934 and made clear his distaste for imperialism that had developed during his time with the Indian Imperial Police. He became a teacher and an assistant in second hand bookshops to support himself, which he wrote about in Keeping the Aspidistra Flying.

He volunteered to fight for the Republicans against Franco’s Nationalist uprising in Spain’s Civil War. He fought as an infantryman in the far-left non-Stalin POUM – the Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification. He wrote about those experiences in a non-fiction piece entitled Homage to Catalonia. He was shot in the neck in 1937 and wrote an essay called “Shot by a Fascist Sniper” about the experience. He left Spain with his wife, Eileen, narrowly missing being arrested when the communists tried to suppress POUM.

Back in England, he supported himself by writing book reviews for New English Weekly until 1940. He was a member of the Home Guard during WWII and began working for the BBC on programs produced for the war effort. He knew he was producing propaganda and, despite generous pay, he resigned from the BBC in 1943 to become literary editor of the Tribune.