Other changes in our adaptation of ROMEO & JULIET

There isn’t really any such thing as a “spoiler” in a well-known story, but you might want to read this post after you see the show, so that its impact isn’t diminished by anticipation.

——————–

- Shakespeare calls for a “Chorus” to speak the opening speech. But he abandons that convention after the first act and Chorus disappears. With another tip of the hat to Larry Life’s 1976 production, I severely edited the prologue and gave the lines to Friar Lawrence, who also ends the play. (The final quatrain in Shakespeare’s version is spoken by the Prince. But I find it more emotionally satisfying coming from the Friar.)

2. The Capulet servant in Act I, Scene 1 is supposed to be called Samson. But he (and Gregory) disappear, never to be seen again. However, Peter has a recurring small role as the clownish, illiterate servant, following the Nurse around, delivering invitations for Capulet, etc. And in the scene in which Mercutio teases the Nurse, Peter protests that he is always ready to fight “if the law be on my side”…which was a primary concern for the servant in Scene 1. Convinced therefore, that Samson is actually Peter, I made the change.

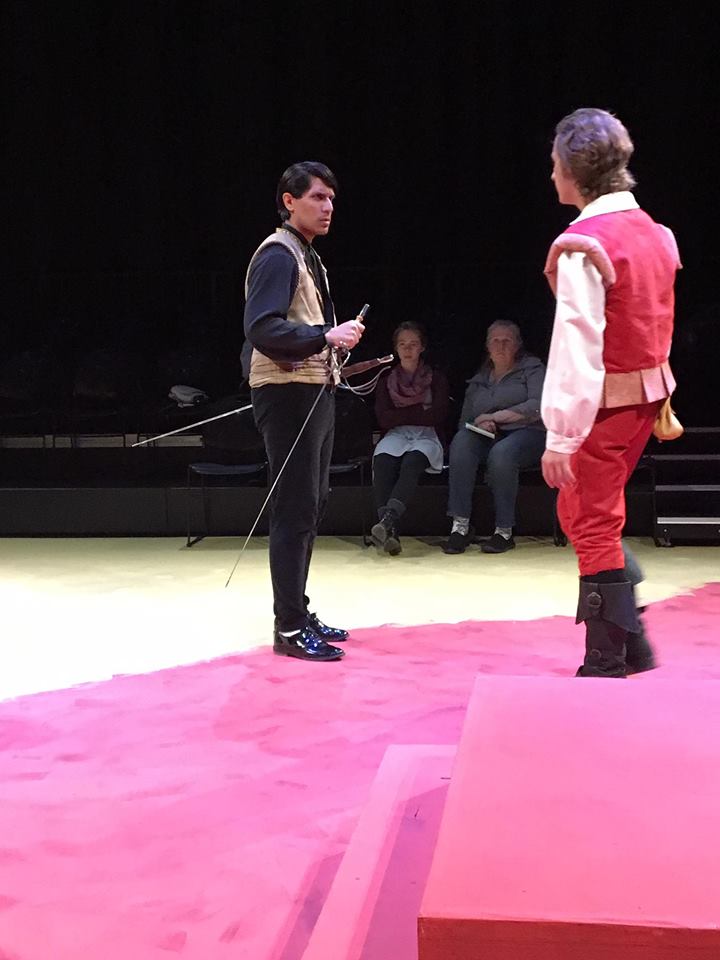

I did not want Romeo carrying a sword at his wedding. He goes directly from there to the fight with Tybalt, so we solved it this way: When Tybalt says “Turn and draw!” Romeo involuntarily reaches for his sword and realizes he doesn’t have it. Tybalt gestures to his page who immediately turns over his own sword. Tybalt offers it to Romeo, and as Romeo says his line refusing to fight, he is also gently pushing the hilt of the sword back toward Tybalt. This served to underscore Romeo’s absolute refusal to fight the man who just became “family” (unbeknownst to Tybalt!).

4. Two scenes in Act V are combined: the scene where Balthasar tells Romeo that Juliet is dead, and the following, where Friar John informs Friar Lawrence that he was unable to deliver a letter to Romeo. By intercutting the two scenes several times, we get a stronger sense of the missed communication and the urgency in both places.

6. Lady Montague dies. I sometimes think Shakespeare had a quota to reach in order to achieve an acceptable tragedy. I can hear his fellow Kings’ Men saying, “Will, the body count is too low.” On the other hand, this particular death may be because the boy actor didn’t want to get back into drag for one lousy scene (or because he was also playing a member of the Watch). Lady Montague is supposed to die offstage of a broken heart because Romeo is exiled. The actress already has so little to do, I felt it was kinder–as well as more dramatically satisfying–to allow her to grieve at the end, and be part of the reconciliation which is portrayed wordlessly (see below).

7. The original ending includes speeches by both fathers about the statues they will raise to the memory of the dead young people. This has been cut in favor of a wordless epilogue in which reconciliation is begun between the sets of parents. The final section of the epilogue, when all the members of the two houses are intermingled around the dead couple, grew out of my settled desire not to have two corpses have to scramble to their feet in the dark and get offstage before a curtain call. By having the whole cast onstage at the end, we could do something much quicker and simpler (not to mention safer!).

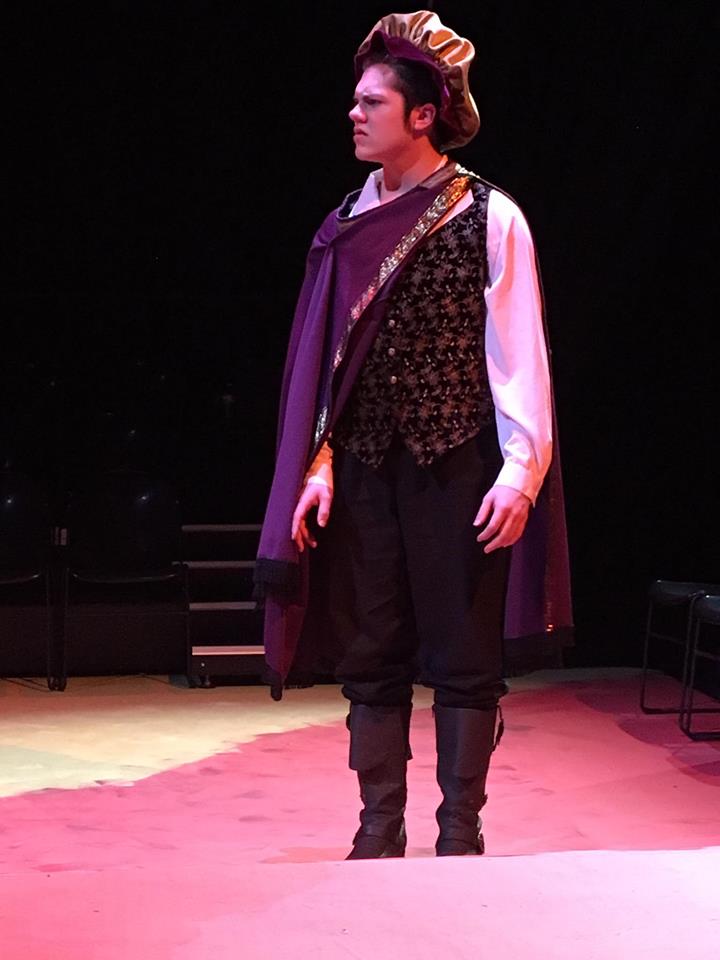

Since we had created house “capes” for everyone for the Prologue pantomime, it seemed right and balanced to bring them back at the end. Having the houses come from opposite sides, as at the beginning, and circle around the bodies, but then begin to merge so that they ended up alternating colors in a ring, worked even better than I’d hoped–once we figured out exactly how to make it come out even every time. One of my favorite moments is when the whole company kneels around the bodies right on the last bar of the music.