ROMEO & JULIET: Of Capulets and Capitalism, part 1

———————–

Nate first offers some background to the social and political setting of the play:

Shortly before 1000 AD an odd phenomenon started taking place in Italy. People started to immigrate into Italian cities in large numbers. Now in most feudal societies of the era that kind of mass immigration was impossible – you swore your allegiance to a feudal landlord quite early, and paid rent on the land you worked for the rest of your life when you weren’t serving as a foot soldier in your liege’s army. But in  Italy, city denizens – or citizens for short – were freed of their allegiance by virtue of living behind really thick walls and the assurances of the city government. This, along with a handful of other guarantees, was one of the first instances of people having rights backed by government.

Italy, city denizens – or citizens for short – were freed of their allegiance by virtue of living behind really thick walls and the assurances of the city government. This, along with a handful of other guarantees, was one of the first instances of people having rights backed by government.

For most people, the principle of being free of a renter’s life wouldn’t be enough to convince them to uproot from the familiar and go somewhere else. But Italy was the doorway to the East, a major hub of trade, and its tradesmen and merchants became wealthy on the transport and sale of goods. The wealthy merchants and guilds of Italian cities needed more workers and they were willing to provoke the feudal lords to get them. Paying the common folk competitive wages to get them through the city gates was simply part of the process, and most Italian merchants were willing to do it. In order to keep workers on their land, the nobility was also forced to pay its renters more. Thus the free market was invented at about the same time, proving that competition does do its part to help the little guy.

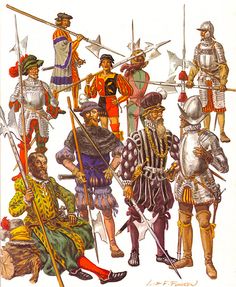

With manpower at such a premium in Italy, training for and fighting wars wasn’t something the Italian city-states had the population for. But they did have a lot of money. So most Italian city-states bought armies, rather than raising them. If finely crafted goods and Eastern imports were Italy’s primary exports, its biggest import – from the rest of Europe, at least – was mercenaries.

But they were still the best trained fighters in Italy and not all of them were foreigners. With wealth offered by the merchants and guild masters of the Italian city states, there were those native Italians who took up the mantle and fought for their native cities – or others.

By the early 1600s, Italy had settled down somewhat and looked more like the rest of Europe, with a handful of major cities controlling large swaths of the nation. But the merchants still had as much political power as the nobility (if not more), and mercenaries were still very much in vogue. It’s not clear how much William Shakespeare knew about the political and economic realities of his time but, with the Renaissance winding down, Italy would still have held a privileged place in European culture, such that he wouldn’t necessarily have to have visited there to have known a great deal about it.